Article written by Isabelle Chéry and Gaëlle Calvary

Definition

A trademark identifies a company’s products or services. For example, Grenoble INP is the brand name of the Grenoble Polytechnic Institute, the legal structure of the engineering and management institute of Grenoble Alpes University. According to Article L711-1 of the Intellectual Property Code (CPI), an article amended by the May 2019 Plan d'Action pour la Croissance et la Transformation des Entreprises (PACTE) law: “A trademark or service mark is a sign used to distinguish a natural or legal person’s goods or services from those of other natural or legal persons. It must be possible to represent this sign in the national trade mark register in such a way as to enable any person to determine precisely and clearly the subject matter of the protection conferred on its proprietor.” The trademark is therefore the acronym under which a product or service is named and marketed. It is part of the company’s strategy: affixed to its products and services, it attracts customers, which is decisive in a competitive environment.

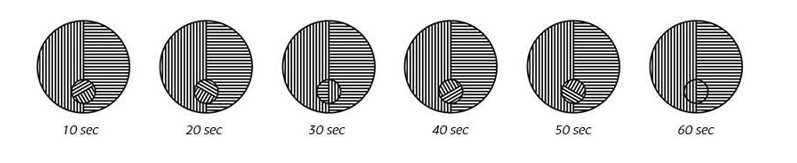

Signs can be names, i.e., words, combinations of words (“you can find everything at the Samaritaine”), patronymic names (“Yves Saint Laurent”) and geographical names (“Evian”), pseudonyms, letters, numbers (“2008”, “205”, “N°5 de Chanel”), acronyms, invented names (“Coca-Cola”). These are then word marks. Signs can also be drawings, labels, stamps, holograms, logos, computer-generated images, shapes, shades or colours combinations: they are called figurative marks. An example is the swooch in the “Nike” trademark. The mark can be complex, with a composition of words and graphics, or even three-dimensional, like the “Perrier” bottle. The mark can also be in motion, i.e., by changing the position of its elements, as illustrated below.

Example by Carl Suchy & Söhne - extract from INPI

There is also the pattern mark, which is characterised by the regular repetition of a set of elements, and the position mark, which is characterised by the specific way in which it is placed or affixed to the product. Trademarks can be sound signs such as sounds or musical phrases. Indeed, until the latest changes in the PACTE law, it was necessary for the sound to be registered with a graphic representation such as a notes staff for example or a lion for the roar of the lion. Indeed, the trademark was previously defined as “a sign capable of being represented graphically”. From now on, the requirement of a graphic representation is removed. This development makes it possible to register sound or moving trademarks in new formats, such as MP3 or MP4, with the Institut National de la Propriété Industrielle without graphic representation. It also makes it possible to protect new types of trademarks such as multimedia trademarks, i.e., combinations of images and sounds.

The sign need not be original or new. It is therefore possible to register a trade mark with existing terms such as “The little black dress” for a perfume.

In addition to the sign, the trademark must define the product or service it designates: a trademark is a “sign + product/service” pair. The possible products and services are listed in the Nice International Classification. This classification comprises 34 classes of goods and 11 classes of services.

Thus, there is nothing to prevent two identical trademarks from legally coexisting, if they concern different goods or services, without any risk of confusion. It is thus possible to have different owners of the same trade mark name for different goods and services. For example, the “Mont Blanc” trademark is held by different owners depending on the associated product and/or service: pen, dessert, mineral water, television channel, transport, university, etc.

There is an exception to this speciality principle: the well-known trademark. A well-known trademark is a trademark whose reputation allows it to benefit from a separate protection under trademark law: in particular, it does not need to be registered in order to be protected; nor does it associate any goods or services. For example, the Coca-Cola trademark is definitely a well-known trademark: it could not be registered for other products.

Conditions for the trademark validity

In order for the trademark owner to obtain a valid trademark registration, it is necessary that the trademark has a distinctive character (Article L. 711-2 of the IPC). Therefore, the trademark must not be descriptive. The notion of distinctiveness is therefore to be assessed in relation to the associated goods and services. For example, the "stallion" mark for a toothpaste is indeed distinctive, but this mark would not be admissible for a horse-riding magazine. The mark must not be customary in the current language or in the bona fide and established practices of the trade, i.e., it must be a commonly used term. For example, the name of the molecule for a generic drug or “entrecôte” for the name of a meat restaurant could not be registered as a trade mark. If it were, no pharmaceutical company could put the name of the molecule on its medicines and no restaurant owner could put “entrecôte” on his menu. The trade mark must be lawful, i.e., its use must not be prohibited. In particular, the mark must not be contrary to public morality and order. The trade mark must not consist of prohibited signs such as flags, state emblems, official hallmarks as well as emblems such as the red cross, the Olympic motto, etc. It must also not contain any misleading sign which would make it a deceptive mark. For example, “Prepharm” for non-pharmaceutical cosmetics or “Lainé” for a cotton carpet. It is obvious that the mark would mislead the consumer about the product. Finally, the trademark must be available, i.e., it must not infringe on the prior rights of third parties. It must therefore be ensured that no one else has registered it for the goods or services in question.

Rights vested in the holder

According to Article L.712-1 of the IPC, "ownership of a trademark is acquired by registration". Thus, the trademark belongs to the first applicant.

Like a patent, a trademark confers on its owner an exclusive exploitation right, i.e., an exploitation monopoly. The protection of a trademark lasts for 10 years, a period that can be renewed indefinitely.

Trade mark protection is territorial. It is therefore necessary for the trademark owner to file applications in each country where he wishes to obtain an ownership title. In practice, the owner will protect himself in the countries where the company has its markets, customers or future licensees.